In the U.S. housing system, single-family (1–4 unit) rental housing is essential because it gives families who are unable or unwilling to purchase a home a place to live. According to a study from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), about two-thirds of the approximately 14 million such rentals in the U.S. are starter-home-style homes, which usually have three to four bedrooms and average prices of $300,000 with rents close to $1,800.

Large institutional investors, also known as “Wall Street landlords,” have recently drawn public attention for purportedly pushing out first-time purchasers by purchasing single-family homes. Whether federal mortgage finance policy should support small-scale investors vying for the same starter houses that first-time buyers are looking for is the more relevant question.

Top Takeaways:

- The primary investor channel is overlooked when policies concentrate on big institutional investors.

- The playing field is skewed by federal policy in favor of small investors rather than big institutions.

- For the same homes, FHA borrowers face direct competition from small investors sponsored by the GSE.

- Even when the residences are similar, U.S. borrowers differ greatly.

- Investors benefit from a long-term pricing and bidding advantage because to GSE financing.

- Homes were made available to owner-occupants when GSE support was decreased.

- First-time purchasers would have greater access if GSE policy was refocused on homeownership.

The main policy concern at the forefront of the subject is how federal mortgage financing affects competitiveness for starter homes.

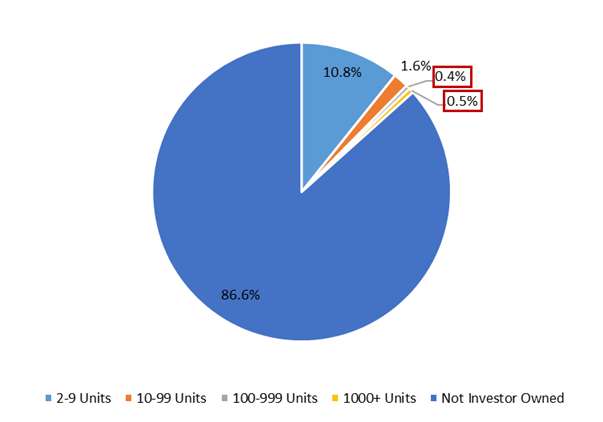

Investor-Owned Share of Single-Family Housing Stock in June 2025 by Portfolio Size:

Note: AEI defines institutional investors as entities that own more than 100 units. These are circled in red, with their combined shares add up to 1% (0.44% + 0.54%).

Expanding Homeownership

Single-family homes are a popular choice for working families and frequently the sole choice for households with children because they provide greater space at a lower cost per bedroom than many apartments. Approximately 60% of low-income wage earner—or 9.9 million people—rent and reside in single-family dwellings, giving them a slice of what homeownership can feel like.

Many of these households are not on the margin of buying; a significant share would not be able to qualify for a mortgage due to underwriting restrictions pertaining to credit, income instability, and documentation. It would be expensive and difficult for them to lose access to single-family rental housing.

So what is the solution to this? The answer is simple: more family-sized supply.

Homeownership remains far away for many renters. According to estimates from Amherst, a major single-family rental operator with institutional investors, over 85% of its tenants would not be eligible for a mortgage because of underwriting obstacles, income instability, or credit limitations. Losing access to single-family rental property would be expensive and disruptive for these households, as the cost of moving and finding new accommodation alone frequently amounts to several thousand dollars.

These figures highlight a crucial point: rental housing itself is not the policy issue. Millions of households rely on single-family rentals to meet their essential needs. In particular, when government-backed credit lowers investors’ cost of capital and increases their ability to outbid FHA and other first-time borrowers for starter-home stock, the more relevant question is whether federal mortgage finance policy should subsidize small-scale investors vying for the same starter homes sought by first-time buyers.

Modest-scale investors make up a far larger portion of the single-family housing stock nationwide, while institutional ownership continues to represent a modest portion. According to AEI’s examination of Parcl Labs data, “mom-and-pop” investors who own fewer than nine homes in their portfolios own around 10.8% of the single-family stock, while huge institutional investors own roughly 1%. Crucially, the GSE channel accounted for almost 40% of small-investor transactions between 2018 and 2024. This suggests that the primary lever influencing investor demand, particularly in the starter house segments where first-time buyers most directly compete, is regulatory decisions limiting GSE eligibility and pricing rather than ownership concentration among a limited number of major corporations.

Although larger institutions are thought to have an advantage since they accept cash, their overall influence is limited by their modest size. The size of small investors and their access to advantageous GSE-backed financing make them a more significant source of competition because it increases their capacity to outbid first-time purchasers. This study demonstrates that the main policy lever influencing investor competition for starter houses is government-backed mortgage financing rather than institutional ownership concentration.

GSE Investors & FHA Borrowers Competing for the Same Homes

FHA owner-occupants and GSE-financed investors sometimes target the same starter homes in the same communities, which runs counter to the idea that investors operate in a separate section of the housing market. Average purchase prices are very similar when HMDA data is used and county-level variations are taken into account. For example, the average FHA owner-occupied purchase is $326,000, while the average GSE-financed investor buy is $336,000.

The overlap of neighborhoods is equally noticeable. For FHA owner-occupied purchases, the median tract-to-MSA income ratio is 95%, whereas for GSE investor purchases, it is 96%. To put it briefly, the two groups are purchasing in areas where the relative income levels are almost equal.

In 2023, GSE-backed investors will make up 22% of all transactions in about 26,000 census tracts containing at least five FHA owner-occupied or GSE-financed investor purchase loans. In other words, there is approximately one GSE-financed investor purchase for every four FHA owner-occupied purchases in these neighborhoods, indicating that investors are a frequent rival bidder rather than an infrequent presence.

Throughout market cycles, purchases by GSE investors have continuously accounted for between 15 and 25 percent of FHA owner-occupied buy activity. Investor purchases financed through the GSE channel continue to be significant even in times of market crisis or when FHA volumes are dropping. This persistence suggests that a significant and continuous portion of the starter housing supply is being diverted from prospective first-time purchasers.

Even though FHA owner-occupants and GSE-financed investors frequently target comparable homes in the same communities, the borrowers themselves are very different. Compared to FHA owner-occupants, GSE investor borrowers are less diverse, older, and earn more money within the same local markets. For instance, the median FHA borrower, who is probably crowded out, made roughly $90,000 in 2023, while the median GSE investor made $170,000. These variations result in much higher financial capacity, which enables investors to compete more fiercely for starter houses.

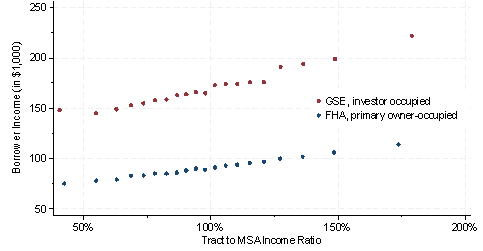

Even within the same counties and neighborhoods, there are significant income disparities. After adjusting for county, the median income of a GSE non-owner-occupied (NOO) borrower in 2023 is around 90% greater than that of an average FHA primary owner-occupied (POO) borrower, and the average NOO borrower’s income is nearly 110% higher. The salaries of GSE investor borrowers are about twice as high as those of FHA borrowers, and they climb more sharply as local income rises. Higher-income households outbid prospective owner-occupants for comparable housing stock by using subsidized credit, which is consistent with this pattern.

Average Borrower Income by Tract Income in 2023:

Note: The figure is a binned scatterplot showing average values within equal-sized bins of the x-axis variable.

Borrower Demographics Vary Across the Board

Age profiles vary as well. GSE investor borrowers are generally 15–20 years older than FHA owner-occupants, according to HMDA age bins, which supports the idea that these investor purchases are usually made by more established households.

The demographics of borrowers also vary significantly. Compared to GSE investor financing, FHA lending serves a far wider range of families. While only 20% of GSE investor borrowers identify as Black or Hispanic, 48% of FHA owner-occupied borrowers do. Roughly 60% of GSE investor acquisitions are made by non-Hispanic-white borrowers, compared to some 49% of FHA owner-occupied purchases. Additionally, Asian borrowers make approximately 19% of GSE investor loans, compared to 2% of FHA owner-occupied loans. In general, minority households are disproportionately served by FHA lending, whereas higher-income, non-Hispanic white, and Asian borrowers make up the majority of GSE investor lending.

Borrower Race and Ethnicity: FHA Owner-Occupied vs GSE Investor Borrowers in 2023

| Demographic | FHA Owner Occupied Loans | GSE Investor Loans |

| American Indian | 1% | 0% |

| Asian | 2% | 19% |

| Black | 17% | 6% |

| Hispanic | 31% | 14% |

| Pacific Islander | 0% | 0% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 49% | 60% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

The cost of financing is one of the main reasons why investors might outbid first-time purchasers. The interest rates given by private lenders today are around 90 to 100 basis points higher than those of the GSE for otherwise equivalent investor loans. County and combined loan-to-value (CLTV) variations are controlled for in this comparison. The observed disparity persists across loan sizes and cannot be accounted for by discernible variations in borrower risk. Rather than loan features, the spread’s constancy across loan-size bins suggests a structural price wedge based on government-backed funding.

It follows that GSE financing offers investors a long-term, rather than merely a short-term, cost-of-capital benefit. Although their rates are far higher, private lenders create investor loans that are functionally comparable. When investors compete for starter homes against FHA and first-time buyers, that subsidized financing directly translates into bidding power.

For example, take a $250,000 mortgage to get a sense of the size. For a particular monthly payment, a 7% rate rather than an 8% rate reduces the principal-and-interest payment by around $170 (about $2,000 annually) and increases borrowing capacity by nearly 10%. That disparity can easily decide who wins a bid in a competitive housing market, which helps to explain why FHA first-time buyers find it difficult to compete with GSE-financed investors.

Overall, data clearly shows that competition for starter homes is significantly shaped by government-backed mortgage financing. Current GSE rules strengthen investor bidding power and limit access for first-time purchasers by lowering investors’ cost of capital. Opportunities for FHA and first-time borrowers would be significantly increased by reorienting GSE policy toward homeownership.

Evidence from previous policy changes demonstrates that when GSE support for investor purchases is removed, investor demand declines and private lenders do not fully restore the lost credit, making properties available to prospective owner-occupants without displacing rental housing. Therefore, refocusing the GSEs on their homeownership purpose would increase first-time buyers’ access to starter houses while maintaining the crucial role single-family rentals play in the housing market.

To read more, click here.

The post Subsidized Credit Gives Rental Investors a Bidding Edge first appeared on The MortgagePoint.